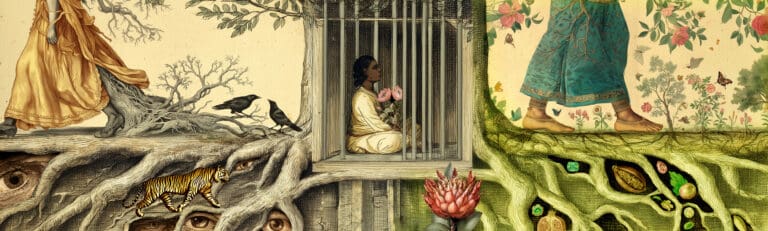

In these times of polycrisis—where ecological collapse, systemic inequality, and a loss of communal meaning intertwine in a spiral of destruction and disharmony—the dominant economic model continues to operate like a devouring machine.

In the face of such voracity, we must urgently turn our gaze toward those who have maintained, for centuries, a reciprocal relationship with the Earth. Indigenous peoples, guardians of biodiversity and life itself, are a model of resilience. They not only resist the violent imposition of a foreign system, but offer concrete pathways that allow us to re-create our existence as a species on this planet. And yet, their knowledge is still relegated to the anecdotal and folkloric, excluded from the spaces where decisions are made about rivers, forests, and climate.

While capitalist logic reduces territories to “natural resources,” Indigenous peoples see rivers, mountains, and trees as beings with whom they’ve woven relationships of mutual care. This is not a mere semantic difference—it is a profound, structural one that shapes the decisions of every human being.

In Cauca, Colombia, for example, the Nasa people protect the river not because it is “economically useful,” but because it is an ancestor, a teacher, a guide that has historically offered them life lessons. They care for it as part of their own community. This worldview, as Ailton Krenak points out, reveals the great failure of modernity: the estrangement between humans and the Earth—the illusion that we are separate from the web of life.

Indigenous knowledge systems could be compared to sophisticated, deep environmental interpretation technologies. Elders read nature’s signs with a precision that challenges scientific instruments: predicting droughts by watching birds’ flight patterns, the behavior of crops; diagnosing a forest’s health by listening to insects; transmitting ecological laws through stories that have been weaving memory for centuries. Yet, these knowings rarely appear in technical reports, public policy, or debates about the planet’s future.

Community environmental monitoring, in this context, becomes an act of resistance and creation. In places like Guaico Alizal, a territory that cares for the Ovejas River, it’s not only about measuring turbidity, dissolved oxygen, or pH levels with sophisticated equipment—it’s about understanding what the river’s deterioration means for collective life.

When a grandmother recalls how the river once flowed full of fish, when an elder shares how the harvests have changed, when a child tells you the river feels sad, they are offering data just as valuable as satellite imagery or spreadsheets. Here, children, youth, and elders document the territory together, combining scientific methods with oral storytelling—because defending life cannot be reduced to statistics.

Defending territory is not just a fight against mining or monocultures; it is a battle for the very meaning of existence. While the industrialized world insists on separating humans from nature, Indigenous peoples remind us that we are part of the same living fabric. Community environmental monitoring is a political act because it shows that another science is possible—one that does not extract, but dialogues; one that does not reduce life to data, but honors it as a network of sacred relationships.

As Krenak writes, “the divorce between humans and the planet is suicide.” In the face of this crisis, Indigenous knowledge is not just an alternative, but an urgency. Listening to the river, learning from animals and plants, honoring the memory of elders—in these seemingly small gestures lies the possibility of a future where Earth remains, as the Nasa say, “the great house that sustains us all.”

Even with languages that paper cannot contain, Indigenous peoples are already writing on the land the path of eternity—the route to survive across space and time.

Poem: Being Nasa

If I tell you I am a child of thunder, you laugh.

If I confess I was born of a lagoon, you whisper “madness.”

But—and pardon me—it is you who are mad,

for not recognizing the blood in your veins,

the murmur of water in your thoughts.

Mad,

those of you who insist on forgetting

that there is no true boundary between skin and earth,

between breath and wind.

You,

who walk as if you were strangers,

as if nature were something external—

a painting, an object, a tool, a resource.

And what should I feel

when my veins sing the songs of my ancestors,

who too were born of thunder and lagoon?

What should I feel knowing

each step I take echoes with ancient voices,

that within my body lives the memory of deep roots?

Do you think that rootedness is a burden,

something to cast off in order to move faster?

Do you think that caring for life is just another task,

a line on a checklist,

an extra job paid with indifference

and forgotten in the chaos?

Gather your roots.

Sink your feet in the wet earth and feel—

not just with the senses you know,

but with those you’ve forgotten,

with those still asleep,

with those still waiting to awaken.

Feel the life that courses through you,

like thunder,

like water,

like the Nasas.

About the Author

ORA Latin America Fellow Jeferson Panche Chocué is a biologist from the Nasa people of Cauca, Colombia, whose work bridges academic science and ancestral wisdom. Trained in biological sciences with a focus on entomology and water quality, he has conducted extensive research in the Amazon and beyond. Rooted in his deep love for his land and people, Jeferson founded a Community Environmental Monitoring initiative that weaves together traditional knowledge and scientific inquiry to protect Mother Earth. His work stands as a powerful act of resistance and reverence for the living world.