Not Many Know Me

Not many know me

For they only know my exterior

Amidst people who are unaware of reality

I remain the unseeing eye.

Who desires me?

Those who do, only want my body

Not my heart

I seek a toe-hold

Not felicity.

Why are they so blind?

If I can quench the physical hunger

Why not be a part of life?

I exist as an individual

but why not as a companion?

You say I bring luck

Can I not be a support?

I am an instance

Why not a livelihood?

I am called the eternal bride

Why not a wife?

I am a mother

But why not a woman.

I am for the sight

Why not for the truth?

I am in the open plain

Why not for life’s caravan?

I am a body

Why not for a purpose?

I am imprisoned

Waiting for the deliverance.

This poem is not a plea. It is a truth spoken aloud.

The title, alone, speaks a hard truth. Not many truly know me. At a time when there were no clear narratives about trans communities or trans culture, there were also no clear answers about my own sex and gender. I existed in uncertainty, shaped not by my truth but by society’s silence.

Only a few understood my feelings. The larger part of society became responsible for my pain—measuring my worth through my body, my suffering, and my attire. I was seen, but never known. My body and my feelings were treated as opposites: my emotions did not fit my body, and my body was denied the right to express my truth.

Living within this dilemma, I slowly came to understand myself in the midst of rejection. A question followed me everywhere: Who will love me when I am neither accepted as a boy nor as a girl? People desired my physicality, but no one was willing to see my heart, my emotions, or my humanity.

I did sex work and begged to fill my stomach—to survive, to live—not for lust or possession, but because exclusion leaves no choices. Even then, I carried dreams: of someone who could call me their own, of a life rooted in belonging.

Why does society refuse to accept us as part of it? Why are we denied friendship, intimacy, and companionship because we carry male bodies and female feelings? From a religious and cultural lens in Indian society, we are treated as lucky charms—invited for rituals, songs, and blessings—yet denied shelter, denied partnership, denied everyday life.

Why can I not be a life partner? I am a mother to many in my community, even without a womb. You seek our presence in ceremonies, our songs in celebrations, our dances in culture—but refuse to recognise us as women in society.

The distance between my feelings and the accepted emotions of men and women remains vast. I have never surrendered my capacity for love, affection, or emotion. Yet I remain imprisoned—allowed to exist only as a body that pleases others. Why can I not be the love they long for?

My poem is motivated by lived experience—by rejection, survival, and the everyday violence of being unseen. It comes from growing up in a society that had no language, space, or respect for trans identities, where my body was constantly questioned and my feelings were dismissed. The pain I write about is not only personal; it is collective.

The poem is shaped by the rejection faced by my community—rejection from families, schools, workplaces, religious spaces, and from the idea of “normal” life itself. When love, affection, companionship, and the right to dream of a family are repeatedly denied, that longing often turns inward and becomes unbearable. In my community, this unfulfilled desire for love and acceptance has too often ended in suicide.

We are told we cannot be loved fully because we cannot bear children or satisfy society’s rigid expectations of gender and family. Our bodies are treated as failures, our lives as incomplete. This denial of dignity is also a denial of rights—the right to love, to live safely, to work with respect, to have shelter, and to belong. This poem becomes a platform to express what cannot be spoken elsewhere. It holds my emotions, my resistance, and my refusal to disappear. It speaks for those who could not survive the weight of rejection, and for those of us still struggling to live with hope. Through this poem, I claim space—not just to exist, but to be recognised as human, deserving of love, rights, and life itself.

The agitation between me, my family, and society has shaped my life, and this journey is woven into my poem. How should readers approach it? My hope is that they read with sensitivity and empathy—toward me and toward the entire community. That they understand the difference between sex and gender, and recognise the emotional, social, and cultural struggles that trans people face. Only then can they truly feel the depth of what is expressed in the poem.

ORA has been a great platform for me. It helped me understand the world better and see myself with more clarity and confidence. I am grateful to ORA for identifying my potential and giving me greater visibility. This journey has meant a lot to me and has become an important part of my growth.

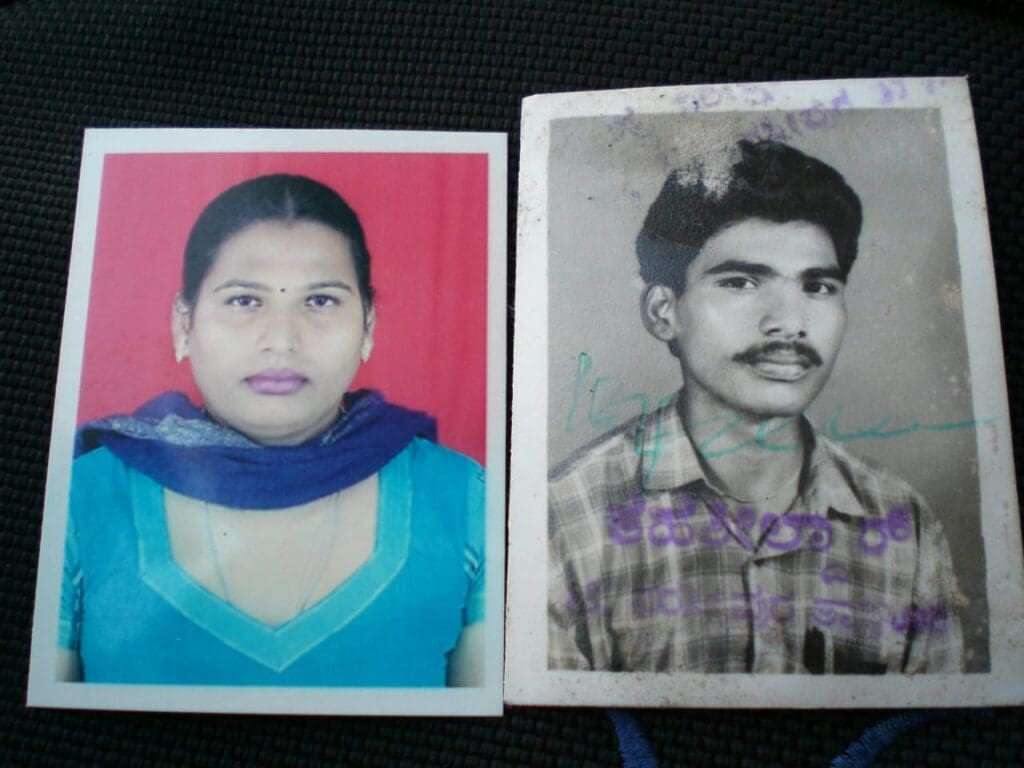

About The Author

ORA India Fellow Chandini is a Dalit trans leader, writer, and performer based in Karnataka, India. For over 15 years, she has advanced the rights, visibility, and self-determination of gender-diverse communities through her leadership of Payana, which has incubated 23 community-based organizations across 28 districts and helped organize more than 10,000 individuals. Her work bridges advocacy and culture—collaborating with government and academic institutions while nurturing artists and storytellers who express the lived realities of their communities.