We arrived in Piñera very early—it was raining and cold, but nothing diminished our excitement to meet the women of the Piñera-Beisso group. When we arrived, most of them were already there: Rogelia, Elvira, Claudia, and Mercedes. Angélica needed a ride, so we went to meet her on the road connecting Piñera with Beisso, surrounded by eucalyptus forests. From previous conversations, we knew it was a hard day for them and for the town—the community was grieving an accident involving a young boy, and that afternoon they would all gather to soothe the sorrow with a collective embrace.

Piñera is a town located in the south of the Paysandú department in Uruguay, within the municipality of Guichón. The community center where the Piñera-Beisso women meet is located there. Beisso is the neighboring town where all the women currently live. Together, both towns have a total population of approximately 400 people. Nearby is the Paso del Salsipuedes, and also Uruguay’s third and largest pulp mill—UPM-2 in Paso de los Toros—which began operations in 2023. It’s worth noting that “Salsipuedes” refers to a historically sacred site, a place of memory that honors the ethnocide of the Charrúa people on April 11, 1831, carried out by Uruguayan government troops under President Fructuoso Rivera.

We introduced ourselves with objects: a palm leaf, a notebook, woven items, a branch of anacahuita. These objects were meaningful and carried stories and emotional connections. The anacahuita offers shelter and is flexible: “Like this branch—when it was a tree, it gave shade and shelter to the family. It represents me because it’s flexible.” The palm leaf, as a native plant, is strong. They are destroyed, and yet they come back to life—insisting on living: “I look at each little palm tree and think of an ancestor… they are alive among us.” The woven items soothe anxiety, connect them to good thoughts, their strengths, to being together: “For me, weaving calms me, it grounds me… I weave even if I have to unravel it the next day.” The notebook becomes a companion on the journey—a witness to learning, thoughts, and dreams: “I brought a notebook where I write everything down. I’m taking a course, and that’s where I take notes.”

These objects symbolize their relationship with nature, with memory, with their families, with their learning processes, with their community—and wool as a companion that weaves them together. Intergenerational ties, their children and grandchildren, are always present in their stories.

Although their group originally formed in connection with the rise of public policies supporting rural women in Uruguay, they have always fought to create autonomous work opportunities for women in their communities. For the past three years, they’ve been meeting at the new community center in Piñera to weave together.

“When you shear a sheep, there are scraps left over. So when you spin, those scraps show up and you have to stop and remove them—you can’t spin with the fleece like that. You have to join pieces together to card it; you card it to be able to spin.”

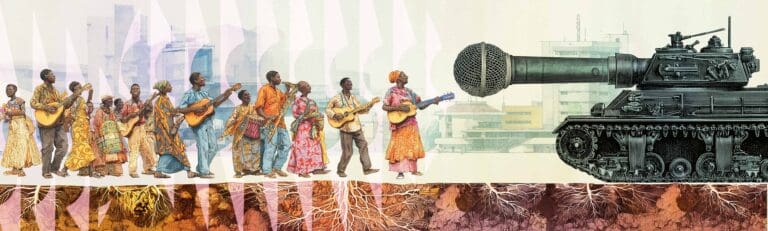

Carding, spinning, and weaving become metaphors for how they care for their communities. They develop collective strategies to keep their knowledge alive, though today they face challenges in marketing their products. Their actions have been key to making visible the struggles of rural women in a context of patriarchal oppression—for instance, through participation in local development councils.

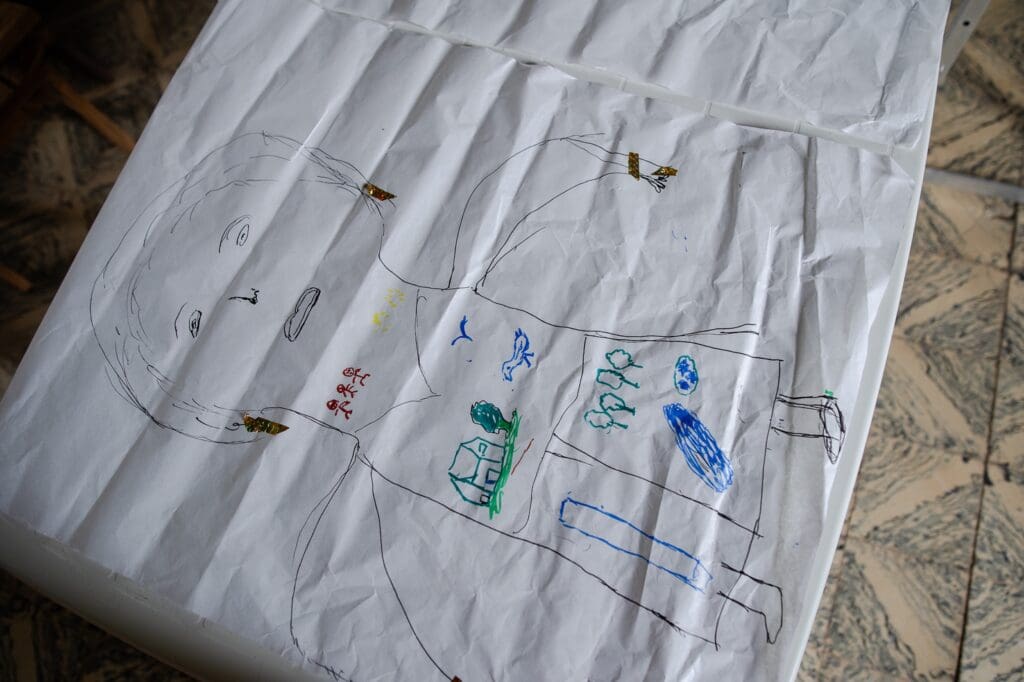

Facing the challenges of our current times, particularly the intensifying extractivism in the region, defending their body-territories takes on new dimensions. In building their body-territory maps, both their strengths and fears emerge—especially fear of speaking out about the problems in the places they inhabit. Health issues, lack of access to jobs, and environmental contamination are concentrated in this region.

As they say:

“We harm the territory outside and we harm our own bodies, because this misuse, this lack of care for biodiversity brings us health problems.” Their health is closely tied to the impacts of forestry and soy monocultures: “They say it’s safe, but I went to that nursery and it’s sealed off with plastic. It’s like vapor—it’s always there. They say it’s not dangerous. But the plant is soaked. Soaked. And you breathe that in. Some people faint.” In their maps, the tension between productive and reproductive labor also appears: “I was the one running the dairy station, and they never paid me a cent—they paid my husband instead.” Women’s work is less recognized, and reproductive labor is made invisible: “The woman is the one at home—caring, cleaning, raising the kids.”

Community appears on their maps as a conflicted space: “It’s more closed off now, more inward-looking. It doesn’t open up. I feel like if the community were more open, life would be better, we’d have better things.” Yet it is within this same community that they find their homes, their loved ones, their relationships with others and with nature—especially birds, plants, and trees. Their homes live in the heart. Their grandchildren are felt throughout their bodies—in their hands: “Because I always go to them, I’m caring for them.”

The mouth is a place of conflict—about whether to speak or remain silent. There are knots in the throat, bandages on their arms showing how long they can stay sad. Legs reflect their journeys and the pain they carry. Their strength lives in their hands, their shoulders, and the paths they walk to reach the homes of their loved ones: “You have to make paths to reach that strength. You won’t get where you want just sitting at home. You have to make the path.”

We said our goodbyes over lunch—some ravioli they had lovingly prepared for us. The trust we had built by that point, along with the warmth of the meal, opened space for one last conversation—about the intimate experiences of life in the countryside, sealing our shared desire to continue… making paths together.

See the full photo record of the gathering with the Piñera-Beisso collective here:

https://valrodlez25.pixieset.com/pinerabeisso/

About The Authors

We are Lorena Rodríguez Lezica, Gabriela Veras Iglesias, Nat Tommasino Comeseña, and Alicia Migliaro González, from Uruguay, and this work has been carried out in dialogue with the collective Critical Views of Territory from Feminism. The four of us in Uruguay have been walking together through university outreach and as social activists. In this project, we come together to support four different community experiences in various regions of Uruguay.

This narrative is a collective creation of Lorena, Gabriela, Nat and Alicia, who organized the meetings and workshops within the framework of ORA.